[00:00:04] Nina: friend groups and all of the anxiety that goes along with parenting a teen who is dealing with being in a group, not being in a group, not liking their place in the group. Wishing they had a group, wishing they had a smaller group. There’s so many different aspects of teen friend groups we’re going to cover today.

Welcome to Dear Nina: Conversations About Friendship, usually about adult friendships, I cover teen friendships sometimes. And teen friendships do affect our adult friendships with other parents.

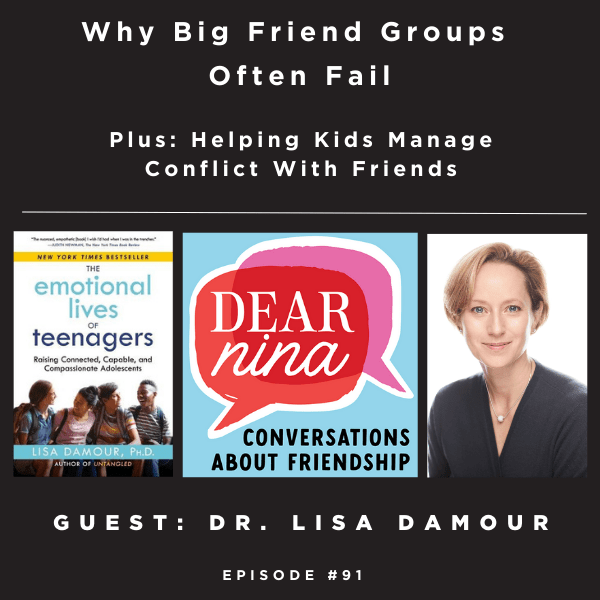

That’s a topic also, how involved to get in all of the ups and downs of our kids friendships. And what happens when you’re friends with the other parents and then the kids aren’t friends anymore. I am thrilled to have an expert on this topic. I spoke to Dr. Lisa Damour when her book, The Emotional Lives of Teenagers came out, her paperback is out. So I wanted to replay that episode, The nuggets that really stayed with me and have helped me since I put that episode out, I’ve heard from others that had helped them.

I also got to hear Dr. Lisa on Armchair Expert with Dax Shepard and Monica. It was really cool to hear that interview. First of all, I love that I had Dr. Lisa first. Let’s just have a moment of that. I also think I might have had Gretchen Rubin on before she was on Armchair Expert. Not that I discovered Gretchen Rubin or Dr. Lisa D amour, listen, if a independent like me can reach out to experts and authors, I have long admired, there is hope for all of us. So I hope that’s just a moment of inspiration that you should go for things that you are interested in and people you want to talk to the answer will not always be yes, but you don’t know, unless you try, just like, I can’t always take on every guest who approaches me.

I get a lot of pitches, but it’s never a bad thing to try and the answer maybe no, but still you might make a connection and a connection that goes beyond social media when you have reached out to someone, even if the answer is no. But back to teen groups, teen friend groups. My podcast is all about friendship.

So that is what Dr. Lisa and I focused on. But her interview on armchair expert, if you’re interested in her background was really wonderful because I just don’t have a chance to do all that in my podcast.

He does a different kind of deep dive and does very long episodes, an hour and a half. That is not for me or for my style. I actually have a hard time even listening to one that long, but I did listen to hers. I Really found it fascinating, her entire background, so I’ll link that in the show notes.

renowned psychologist Dr. Lisa Damour is the New York Times bestselling author of Untangled, Under Pressure, and The Emotional Lives of Teenagers. She is also the co-host of the Ask Lisa podcast, and in this episode we cover accepting that teenage social strife is a normal part of growing up and not something to help kids avoid at all costs.

We discussed that teens will get left out and leave others out as a normal part of growing up. Really cannot protect your kids from that. The solution to kids getting left out is not necessarily the idea that everyone gets invited to everything. The solution might be helping kids and teens and, frankly, adults,

accept that it’s impossible to include everyone in everything. And it’s normal to have a negative emotion about that. But then to move on and make your own plan. We talk about how friend groups seem so formal today. I’ve heard that from a lot of parents.

I feel it too. It seems like the boundaries around a friend group are so set about who’s in and who’s out. instead of wishing it weren’t that way, I think we have to help our kids navigate that. Not easy. Dr. Lisa has some ideas about friend groups, over four kids based on research. You’ll hear that in the episode.

And we talk a bit about mental health: What kind of negative emotions are in the normal range of negative emotions and that our kids are not going to be happy all the time. I hope you get as much out of this conversation with Dr. Lisa as I did, and congrats to her on the success of this book and her previous books, Without further ado, Dr. Lisa,

[00:04:01] Lisa: thank you so much for having me.

[00:04:03] Nina: I love your podcast with your friend, Rena. Before we really get into the teen stuff, I just want to tell you, you both have such pleasing voices , it’s just a great podcast and so practical.

[00:04:13] Lisa: Thank you. We really do try to just meet parents where they are and answer the questions that are top of mind.

[00:04:19] Nina: And do you both live in Cleveland?

[00:04:21] Lisa: I live in the suburbs of Cleveland. She lives in Connecticut.

[00:04:23] Nina: Okay, so it’s a long distance

[00:04:25] Lisa: Yeah, but it works.

I’d love for you to help listeners understand the context for your newest book. What had you been noticing about the way adults approach teen distress nowadays that made you want to write this particular book?

[00:04:36] Lisa: So the big issue that we’re struggling with as a culture and that then trickles down into parenting and into raising teenagers, is that, in our culture, mental health has come to be equated with feeling good or relaxed or happy, you know, feeling, , comfortable with oneself and.

, these are all wonderful things, but they’re not actually what mental health is What I wanted to bring across in the book was the idea that comes from, you know, I’m a psychologist, how we think about things on the academic and clinical side, that being mentally healthy is about having feelings that fit the circumstance and then managing those feelings well, even if those are negative emotions.

so that was the main driver behind writing this book is that I wanted to give parents a framework for allowing negative emotions back in not feeling so frightened of negative emotions in teenagers. Understanding that they are often are evidence of mental health. If something goes wrong and a kid’s upset, that’s actually a good sign.

That they’re having a feeling that fits the circumstance, and I think that it’s a lot easier to do that as a parent if you also feel like you’ve got a great repertoire for helping the kid manage those emotions. And so the book is some about, you know, how do we make sense of distress? How do we know when it’s typical and expectable and growth giving and healthy, and how do we know when it’s not? And how do we help kids throw it?

[00:05:53] Nina: It’s so helpful and there’s a lot of strategies in the book, so I really encourage, parents of teenagers to buy it. There was a line in here in the book, \ I underlined many lines, but I just want to read one that really just echoes everything you said and I said in the intro, which is this book will ditch the dangerous view that adolescents are mentally healthy only when they can sustain a sense of feeling good.

[00:06:14] Lisa: Yep.

[00:06:14] Nina: That’s just a beautiful summary and something we need help with. That unhappiness and strife is necessary for growth. So I wanted to use a pretty benign example of a kid starting middle school or high school. If they’re moving to a new high school and they have no one to sit with at lunch because they don’t know anybody.

Or maybe they know some kids, but not well enough to approach their lunch table. And I’m talking about week one, week two of school, not, you know, I think mid-year that kid still has no one to sit with. Now we’re having a different conversation, but just this kind of. What I call benign strife.

How much does a parent get involved in giving advice or even calling the school? Like what, what do you have parents do?

[00:06:51] Lisa: Well, the first question is how stressed is the kid about it? we gotta start there all the time because if it’s not a problem for the kid, it can’t be a problem for you. You might be worried about it, but if the kid’s like, I don’t know, figure it out or else it’ll all on my own, and they really genuinely seem to like be really ready to take that in stride.

Like we have to be okay with that. Now, if the kid’s like, I’m freaking out. I’m not sure who I’m going to sit with. I don’t know what’s going to happen. Then I think we can brainstorm with them, what ideas do you have about how to, , tackle this? We can also play worst case scenario, right?

Which is, okay, so say you get to lunch and there’s no one to sit with. What’s the plan? Do you know how to take a quick exit to the library? Like, how do you know? What are you going to do? As miserable as it is, to have worries about where one is going to sit at lunch or if one’s going to have company at lunch.

This is well within the range of typical and expectable challenges that come with being a growing person in the world and what our kids need from us more than anything, is a vote of confidence that they’re going to find their way through it, or that they can garner the resources, they can summon the resources to find their way through it. If we, with all of our middle aged experience, treat this as though it is a crisis that actually is more frightening to our kid than anything else.

[00:08:08] Nina: it’s so wise. Exactly. They need to be treated like, yeah, they’ve got this, they can do this with some strategies.

[00:08:14] Lisa: It’s interesting, one of the, phrases I picked up, we have the Peloton app. We don’t have any of the machinery, but we have the app. It’s like a really, wonderfully inexpensive option. And there’s a great, , strength trainer, Andy, who I love, and he says, this should be uncomfortable. It shouldn’t be unmanageable.

[00:08:30] Nina: Oh, that’s good.

[00:08:31] Lisa: It’s brilliant. And so he’s talking about weightlifting, but I’m like, oh, this is how we should think about parenting. Right? Uncomfortable and unmanageable are not the same thing. So walking into a lunchroom and not knowing who one’s going to sit with is uncomfortable, no question.

The question is, is this unmanageable for your child? If it is, what can be done to help them manage it? Or, what else needs to happen so that they’re not in a position that feels untenable for them?

[00:08:54] Nina: a place I see parents get really. Involved and even if it’s not involved in doing anything about it, it’s involved in chatting about it amongst adults is another scenario that has come to me from listeners and it’s, I’ve seen it in my own life too, with all these teens around here, which is, let’s say your teen is part of a homecoming group or a prom group, or it could be a Halloween party.

, this goes on all year long and. It doesn’t include everyone that you as the parent are friendly with, if that makes sense. If you’re following. So, cuz a lot of times in a smaller community or really any size community in a school community, you know, other parents, your kids may be close, maybe aren’t as close anymore, or they kind of ebb and flow in their closeness.

And so for this homecoming outing, this Halloween outing, this prom outing, it does not include everybody. And these groups usually get big, they could be, you know, guys and girls and it’s. Could be 30 kids, but, and that seems like, wow, 30 kids, it should have everyone, but maybe there’s really 40 to 50 kids if we’re talking all kinds of kids that do hang out sometimes in different forms.

This particular group doesn’t include them all. As a parent, I know I feel this way. I immediately guard us up. Somebody’s getting left out. And even if it’s not my kid, I am find myself, and I know my listeners do too on edge because we’re like, okay, now my kid’s doing the exclusive thing, my kid’s doing the leaving out how involved do we get.

[00:10:18] Lisa: Well, what’s interesting is what you’re describing is by the structure of this, there’s already a very high level of parent involvement in adolescent relationships in the friendship groups. And just for compare and contrast, my mom, Had no contact with the parents of my friends, and I was so glad, that would’ve struck me as so strange, right?

That you know, she had a social life, but it had nothing to do with my social life.

[00:10:43] Nina: Same.

[00:10:43] Lisa: Now this is different. we’re into a generational shift there’s much more kind of overlap in terms of the social circles that the adults have and that kids have. This tends to work better when kids are younger.

When parents have more engineering capacity and kids have less very, very strong opinions about who they want to hang out with. What I would say is by the time kids are teenagers, very strong opinions and forces take over in terms of who they want to hang out with and who they don’t. We were the same way, right?

I mean, do you remember as a teenager, like if your parent would be like, oh, so-and-so was coming over and they’re bringing their kid, and I’m sure they’ll get along, you’d be like, I’d rather eat ground glass, right? I haven’t even met the kid, but I don’t want anything to do with this, right? So this is natural to adolescents that they’re trying to find their way and figure out who they’re hanging with, and they figure out, , the kind of the currents and the vicissitudes of that complicated enough as they try to sort it out for themselves.

The parents having skin in this game just adds another layer of complexity to it. So what are we supposed to do? One thing I would say is if you are going to have an overlapping situation where the adults you’re friends with are the parents of kids that your kid is in a social group with, the more that the adults can come to an agreement that what happens among the kids does not actually mean anything in terms of what happens among the adults, the better.

This is easier said than done, but you really want to have these operate independently. The other thing I will say is there’s real value in not having overlap if you can help it. the only reason I knew to do this is because I’ve been a practicing psychologist for so long, but I have, you know, a daughter who’s 19 and a daughter who’s 12.

with my older daughter, there are. Girls she is friends with whose parents I think are fantastic. And I’ve gone out of my way to not have them in my social circle because I’m like, what if our daughters decide they don’t like each other anymore? Like it will just be weird. So I may, now that she’s well into college, I may, you know, that I can entertain the possibility of being friends with those parents.

But I think there’s a lot of people to be friends with. And if you have the degrees of freedom to keep your social life separate from your kid’s social life, I think there’s real value in it.

[00:12:48] Nina: Yeah, and it’s, I, I feel personally, I’ve been on all sides of this when I’ve seen my kids and, , kids of my friends excluded. I’ve seen my kids being the one making those decisions, and I totally agree. You cannot, at a certain point, keep telling the kids who they’re going to hang out with.

And, you know, kids make mistakes. One thing I, I think that troublesome is the way the adults are kind of involved in the teen friendships, not even if they’re pulling any strings or doing anything or micromanaging it anymore. It’s just the level of knowledge we have. I agree, my mom only knew what I told her.

I feel like there’s a lot of chatter and social media doesn’t help. Like even as parents on social media, we can see other kids getting together and you know, I’ve had that thought before. Oh, I wonder if my kid’s seeing that. And then, you know, you kind of are aware that there’s this thing happening and you wonder if they see it.

I know you work with teens, but just as like a fellow mom and, a professional, I wonder, it’s my amateur assumption. If it makes us all think of times we were left out as kids or something. If we get on edge because it’s like we’re hearkening back to our own adolescence, middle school, high school and sort of being forced to, well, not being forced, choosing to relive it in a way

[00:14:00] Nina: through the kids. Do you see some of that?

[00:14:02] Lisa: certainly. You know, having a teenager can poke at old bruises. Right. , and we remember our adolescents pretty vividly. I think that that can happen and I think it can mix things up even further where the parent may be intervening when the kid’s fine, but the parent’s not fine. And you know, that’s again, a question that we want to keep a close eye on.

But the other thing I will say is that kids have always been left out. There’s never been a party that includes everybody and your kid is always leaving people out, right? Because you are not inviting everybody in the whole universe to whatever is happening. What is really lousy these days is everybody knows what they’re being left out of.

Everybody has, real time visual evidence of where they are not included. I think one way we can be really helpful to young people is to empathize with that being the. State of affairs to not try to make sure they’re invited to everything or make sure everyone’s invited to everything.

That’s an impossible aim. But instead to say, you know, this really stinks. You know, there were a lot of things we didn’t have when I was a teenager, but we also didn’t have to do this. If we weren’t included, we did not know, and that was a wonderful, gracious thing. I’m sorry that the nature of the digital environment, Is such now that you, you know, when you’re not included , that’s just too much information and you’ve got it.

[00:15:22] Nina: Yeah, I like that Just to be, again, we see it too as adults. It happens as adults. My other, theory is, that a dults who get really bent outta shape at this point in life about being left out or seeing their teens being left out

are maybe people who didn’t work that out when they were teenagers. Maybe they didn’t have a parent or a teacher or a school counselor or a psychologist say to them, this is a normal part of life. Kind of to the point of your book, like if you could help them understand it’s normal to be left out.

It happens. It’s normal to feel bad about it at any age, but also to move on. Make a plan. You call a friend, you invite someone over.

[00:15:57] Lisa: Exactly back to uncomfortable versus unmanageable, right? I mean, I have had things like events that I’m aware of in my community where I’m like, oh my gosh, I wasn’t invited. And I’m thinking, I mean, I wouldn’t have wanted to go, but like I wasn’t invited. Even at 52 I can have this, like I was left out.

Ouch. You know, of something. I wouldn’t even want to be part of upset. That’s a feeling, that’s a completely unavoidable aspect of being human. Our job as the adults in the picture is to say it’s a feeling. It is uncomfortable. It’s probably not unmanageable. I’m here to help you address it, but we don’t have to leap into action to prevent the experience of the negative emotion.

[00:16:37] Nina: Yes. And the solution is not, I have to say this a lot to adults on my podcast about adult friendships. The solution is not everyone gets included. It actually isn’t. It isn’t the solution.

[00:16:48] Lisa: Well, it’s also, I mean, it’s actually just logistically an impossibility. as soon as you add one more kid, well then that opens the door to two or three other kids who could have been included. I mean, like, it’s just, it’s just, you know, it’s just not how it works. But I think we can know that theoretically when we ourselves or our, our kid is not included , it’s easy to lose that and to just look at the kid who’s in pain and think like, why didn’t you include my kid?

I get that. I really get that.

[00:17:12] Nina: It does, it feels bad. And then I try to remind people you know, how you like sometimes just to get together with one or two people? You have to extend that same grace to other people.

[00:17:22] Lisa: Mm-hmm.

[00:17:22] Nina: . We struggle. I think sometimes as human, it’s just human nature to extend the same, grace to the next person. Like, we give ourselves a lot of breaks. We’re like, oh, we just wanted it to be a small group. But those people were rude and exclusive.

[00:17:34] Lisa: Yep.

That’s, we gotta think about it that way. Exactly.

[00:17:37] Nina: the, last major topic I wanted to talk about with you, because it comes up a lot these days. I had a group of friends in high school. I don’t feel like it was. Formalized, the groups now seem so formal, like it’s almost practically like an official initiation in a lot of different communities.

I hear from people. All around the country. I really do. And they are all echoing the same thing about their teens friend group.

And there was a friend group and then their kid is dropped from the friend group. And how do the kid know they’re dropped? Usually there, there’s a new text thread on Snapchat or maybe. On some other app without this kid now, and that’s kind of how the kid knows. Oh, there’s been all these things kind of, it’s similar to the previous topic about being left out of an event, but now we’re talking an official, you are not invited anymore, ever. What do you do to help kids through

[00:18:32] Lisa: Yeah. You know, it’s interesting, you know, , the term friend group or friendship group, Hasn’t always been one that I heard kids using as much as they use it now. It seems much more kind of crystallized, like you say, as like a thing. Like this is my friend group. This predates the pandemic.

I remember kids talking about it. I would say it’s probably been, , made more intense and brittle by the pandemic. , one thing I can say without question about the pandemic is that it made kids a lot more anxious about who their friends were and who they were hanging out with, and who they were going to call, , their group.

And it’s also made kids, honestly, quite a bit harsher with one another. , less graceful in their handling of conflict, less generous in their assessments of one another. So we’re in a phase right now, and I, really do hope it kind of works it’s way out where the friendship strife I hear is much much more pronounced, much meaner actually than what I’ve heard prior to the pandemic.

So I think that we have to allow, right, if , we share this observation that kids are like, this is my friendship group now this kid is not in my friendship group. Right? Like, these very kind of, you know, rigid decisions are being made. Let’s really make some room that this is kids feeling anxious coming out of the pandemic, and that they need to know who their people are kind of declaring in a formal way:

we are a friendship group, offers some comfort and some reassurance. the key on this is that kids think they want big groups. There’s no big group that works well. And the reason there’s no big group that works well and I’m by big, I mean like more than four kids and four kids is pushing it. It is absolutely impossible for four people or more of any age to like one another equally.

It never works. And so these poor kids are kind of stuck in this dynamic where I think out of fears, post pandemic. Basic insecurities of being a teenager and wanting to make sure you’ve got people to do things with. They coalesce into groups that may have five or six or seven or even bigger than that, and then

drama ensues. Not because they’re bad kids, but because you cannot get a group of five or six or seven or eight who like one another equally. So there will be kids in that group where there’s oil and water, like they just don’t get along. And so then within the group, kids feel recruited to choose one side or another.

There will be subgroups within that group. If you’ve got eight kids, there’s going to be three who really want to hang together. So occasionally they will. And then of course sometimes they will put it up online and then everybody sees it and it feels really lousy. But of course not all eight, , are going to want to hang out together all the time.

What’s the solution here? Here is the solution. Reassure your kid that we have really good data showing that the least stressed kids have one or two good friends. Full stop.

[00:21:12] Nina: Oh, that’s so interesting and I love that you know, all the research in your book and in your work in general. Wow.

[00:21:18] Lisa: Yeah, one or two good friends. And the reason for that is that they have what we call sustainable routines. They know who they’re hanging out with. They know where they’re going to spend their weekend. If , they get some fantastic piece of good news, they know who they’re going to call first. Kids who have these large, extensive friendship groups, which you know your kid’s stuck with.

If they have, they’re not going to be like, You know, and you don’t want them to kick everybody out. They have the additional stressor of, , they can’t include everyone all the time. If you get a piece of information, who do you call first? And then how does the person who heard you told the other person first feel?

I mean, it gets all very complicated, very, very fast. So this is a long way of saying popularity is not that great. It means you got a big social network, but that doesn’t mean you have an easy social network and one or two good buddies. Is often a solution that we see works best for kids.

So if your kid has one or two good buddies, leave it alone. It’s perfect. If your kid has a large pet friendship group, do not assume that anyone is going out of their way to cause trouble. It is the nature of those larger groups.

[00:22:12] Nina: So many good nuggets here. , we’ll end with you. Just anything else that , you would want my audience to know about teen friendships and how to be okay as a parent with your kid having strife in their friendships. How to be okay as the adult.

[00:22:31] Lisa: Well, I’ll see you and I’ll raise you, actually, and this is going to sound like a strange way to say it back, but how to make the most of the fact that your kid is going to have strife in their friendships. So here’s what we have to start with as a shared assumption. Kids are going to run into conflict with their peers and their friends.

They’re not all going to get along all the time. That’s actually an impossible thing. The goal is not the prevention of conflict. The goal is that kids learn how to handle conflict well. And this is something I unpack in a lot of detail in Under Pressure, the book that proceeded, the Emotional Lives of Teenagers.

But the summary on this is that the way I like to teach it to teenagers is that there’s three kinds of healthy conflict. And three kinds of unhealthy conflict. The unhealthy conflict kids recognize immediately. So it’s being a bulldozer, running people over, being a doormat, letting yourself be run over.

And most common being a doormat with spikes engaging in passive aggressive behavior, , which is so common. You can actually. Break it down into categories like using guilt as a weapon, playing the part of the victim involving third parties, and what should really be between two people. Okay? We all have our impulses in that direction.

We all need daydream about all the passive aggressive stuff we want to do. Best not to act on that. If there’s going to be a conflict. One healthy form is to act as a pillar , be assertive. is what that means, to stand up for yourself while being respectful of the other person. If you need to say something, you want to do it in a respectful way,

and that’s important. Another form of healthy conflict is what psychologists call emotional aikido. So in Aikido, when somebody comes at you, the first thing you always do is dodge. You actually just let it go. You, don’t engage it because maybe they’ll go bother somebody else. So they’ll be knocked off balance.

There’s no tactical advantage. So emotional aikido is actually a tactical non-response. Like that kid was being a jerk. I’m not going to interact with them. I’m not going to stand up for myself. It’s not worth it for any variety of reasons, but I’m also not going to engage it, that is a form of a healthy decision just to not engage. The third form if you’re really stuck, right?

If a kid’s really stuck between I don’t want to say something, I don’t want to ignore it. A third form is, what’s the kindest thing a human being could do in this moment? If I just looked at this from the lens of just sheer kindness, what would be the greatest act of kindness I could commit in this moment?

No kid, no adult ever regrets that choice, so I. Plan for conflict. Embrace it when it comes. Use it as an object lesson. Here are all the unhealthy things that a kid would want to do in your shoes. Here are your healthy options. Let’s play it out. What do you want to choose? Nothing from column A. Anything you want from column B, right?

I mean, it’s a gift. So rather than being crouched in a defensive posture, like, I hope my kid’s social life goes great, give that up. It’s never going to happen anyway. Instead be of the mind, okay, conflict’s happening. This is my great grand opportunity to teach my kid how to handle conflict well.

[00:25:15] Nina: Yeah, and to have the confidence in the future, they, they can draw on that confidence that they got through it. I mean, if we rob them of that opportunity to say, Hey, I can do this. I’ve done it, therefore I can do it again. You can’t go into a healthy adult, relationship that way with other adult friends.

You just. You can’t, so we’re going to help our kids do a good job, and probably learn some stuff ourselves as adults that maybe we might have missed out on somehow. Some people do. Some people miss those opportunities when they’re teenagers themselves. Lisa, thank you so much. I will have every place people can find you in the show notes.

I’ve been sharing your work a lot on social media, because I’m just crazy about it and really just honored to have you here. So thank you very much.

[00:25:53] Lisa: Well, the Honor is mine. Thank you for having me.

[00:25:56] Nina: And listeners if you got something out of this episode, and I hope you did, please go ahead and say so on Apple Podcasts. It helps people who are looking for honest and nuanced conversations about friendship to find us. we’re building such a thoughtful community here. I love the conversations that I’m having, not only with guests, but with listeners In our Facebook group, Dear Nina, the group, which you can just find by going into Facebook, going into the search, putting in Dear Nina the group and it will come up it will ask you a question about how you found us because I don’t like to have spam or anything in there, I screen everybody who I let in and by screen I mean it just asks how you found us and if you say the podcast or the newsletter, which is at dearnina.subsack.com.

I’ll let you in. There’s nothing to it but that. Have a great week. I’ll see you at the next episode when our friendships are going well, we are happier all around. Bye.